The yen’s decline turned Japan into a tourist paradise. For months, travelers flooded its streets, drawn by affordable prices, stunning landscapes, and a unique culture. But that boom may be over. This summer, Japan is seeing a dramatic drop in tourism — with bookings down by as much as 83% in some areas, according to recent analyses. The reason? An old manga and a chilling prophecy.

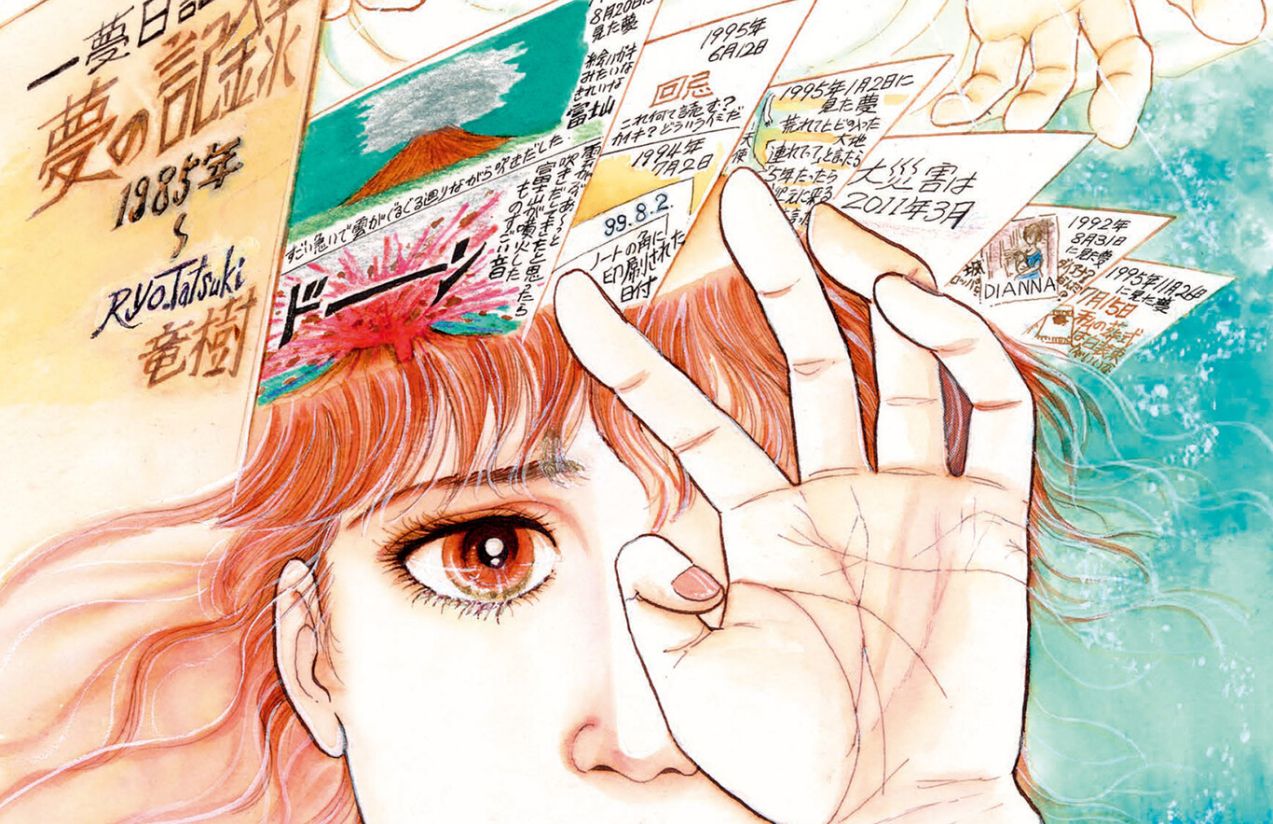

Until recently, nearby countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong were among the biggest contributors to Japan’s tourism surge. Now, those same regions are disappearing from travel forecasts. All because of the resurgence of a comic book published back in 1999: Watashi ga Mita Mirai (“The Future I Saw”) by artist Ryo Tatsuki.

The manga went largely unnoticed for years—until March 2011, when a devastating earthquake and tsunami struck Japan. The media quickly picked up on a haunting line printed on the manga’s cover: “A great disaster will occur in March 2011.” The book, which tells the story of premonitory dreams, had been on shelves for over a decade before the disaster struck.

That eerie coincidence was enough to reignite interest. Readers began scouring the book for other accurate predictions: the deaths of Freddie Mercury and Princess Diana, the 9/11 attacks, even the COVID-19 pandemic. The myth grew. And in 2021, the publisher seized the opportunity with a complete reissue of the manga—this time with a new warning on the cover: “The real disaster will come in July 2025.”

That new prophecy quickly went viral in South Korea, Hong Kong, and beyond, sparking a domino effect. Tourism bookings to Japan plummeted. Even the Chinese embassy issued a public call for calm. The panic isn’t based on any real event, but on a story that’s escaped fiction and begun shaping real-world behavior. It’s a textbook case of hyperstition—a term used to describe how fictional ideas can become reality when enough people believe in them.

Similar phenomena have gained traction in pop culture, with so-called “predictions” from The Simpsons or viral internet memes. Hyperstition turns fiction into a self-fulfilling prophecy. And although Tatsuki recently emerged from retirement to clarify that she never meant to predict the future, her work has had a real-world impact. “I only wanted to make people think. I’m no prophet,” she explained in an interview, while encouraging the public to listen to experts and prepare rationally for possible natural disasters.

But there’s also a psychological side to all this. The fear gripping many is rooted in apophenia, a cognitive phenomenon where people find patterns or connections in unrelated data. When a random prediction appears to come true, our brains tend to remember that moment more strongly than all the ones that didn’t. This is closely tied to the Forer effect, where vague ideas—like “a great disaster is coming”—are interpreted as specific and personal.

While Watashi ga Mita Mirai was likely never intended to do so, it has become a powerful example of how fiction can reshape real-world behavior. In this case, it’s done the unthinkable: it’s brought Japan’s thriving tourism to a standstill. All because of one sentence on a manga cover published over 25 years ago.