Ukrainian forces had long been tracking a peculiar Russian drone—unlike the typical models. It wasn’t just a reconnaissance device or an attack craft; it was a decoy, designed to emit fake radar signals and overwhelm enemy air defenses. But the real surprise came not from intercepting it, but from discovering its origin. The drone, known as Parody, turned out to be not so Russian after all. A similar story now unfolds with a new missile deployed by Moscow on the front: the S8000 Banderol.

Presented as a domestic development, the Banderol has been described by Ukraine’s military intelligence (GUR) as a key piece in the Kremlin’s renewed long-range strike strategy. It is a compact cruise missile, launched from unconventional platforms such as Orion drones—similar in design to the U.S. MQ-1 Predator—and, in the near future, from Mi-28N attack helicopters. Equipped with a small jet engine, retractable wings, and a 110-kilogram warhead, it can reach distances of up to 500 kilometers at cruising speeds of 500 km/h. Its maneuverability strongly suggests it was engineered to evade air defenses more effectively than its predecessors.

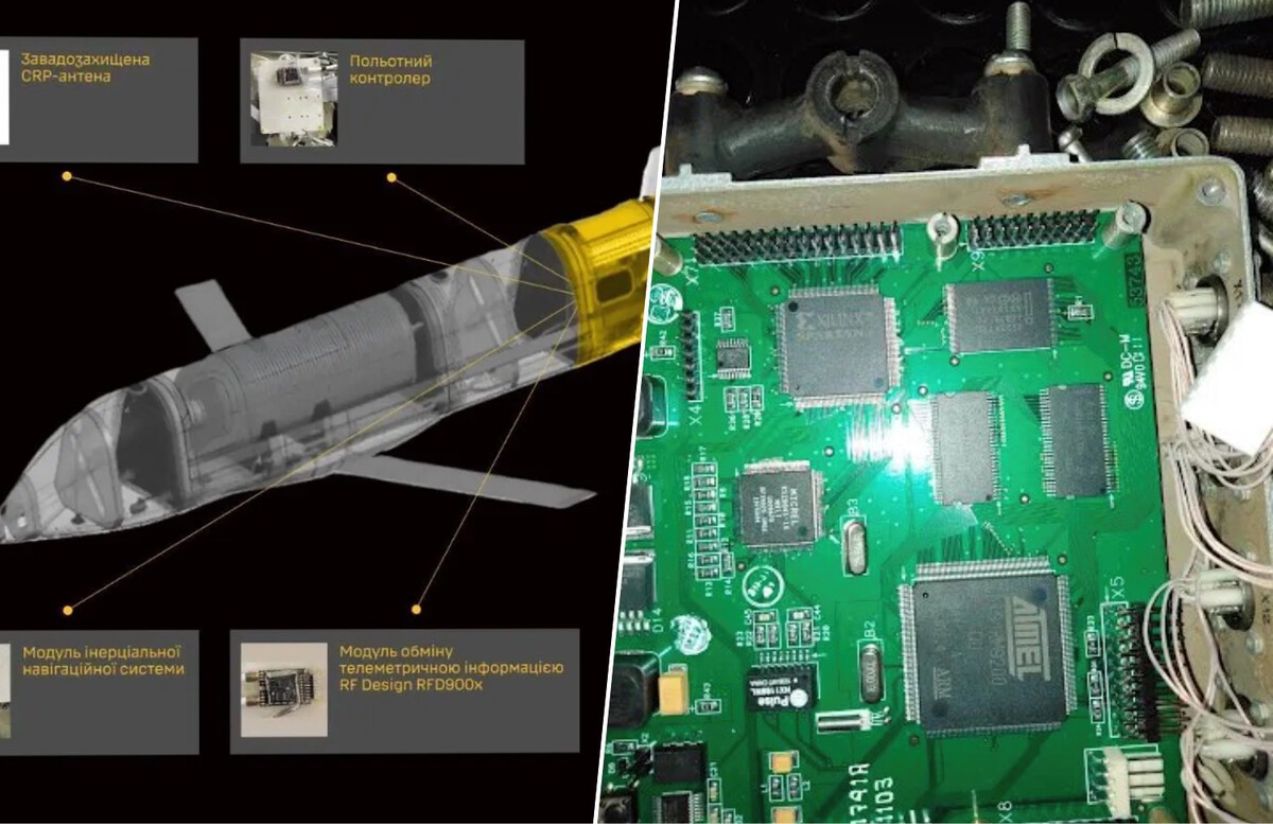

However, the most revealing finding came after technical analysis of several recovered or downed missiles. When dismantling the Banderol, Ukrainian specialists uncovered an uncomfortable truth for Moscow: much of its internal hardware is foreign-made. The propulsion system, for instance, is a SW800Pro engine manufactured by China’s Swiwin and available on platforms like AliExpress. The telemetry module, the RFD900x, originates from Australia. Additional components include Murata batteries (Japan), Robotis Dynamixel servomotors (South Korea), and an inertial navigation system likely of Chinese origin. All of this is topped by nearly twenty microchips in each missile, primarily made in the United States, Switzerland, Japan, South Korea, and China—many acquired via Chip and Dip, one of Russia’s largest electronics distributors, now under sanctions.

Russia’s technological dependence is nothing new, but the sheer volume and sources of these components remain striking. Similar parts have been found in drones like the S-70 Okhotnik-B, in glide bombs, and even in weapons imported from Iran and North Korea. Despite the heavy sanctions imposed by the U.S. and its allies, the Kremlin has maintained a steady flow of sensitive technology through transshipment routes, third-party intermediaries, and the gray market for recycled microelectronics—often centered in China. Many of these parts are derived from civilian products, complicating efforts to trace and restrict their flow.

According to analysts at defense platform TWZ, Russia has spent decades perfecting its evasion techniques. The Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) has already warned that, despite international efforts, certain actors continue to gain access to sensitive technologies through deception and regulatory loopholes.

As for its performance, the Banderol does not rival high-end missiles like the Kh-69, which can carry warheads up to 300 kilograms. But it fulfills its role: a low-cost solution with decent precision and medium-range capabilities, well-suited to the current conflict. Its inertial navigation system, satellite correction, and electronic countermeasure resistance make it an effective tool for saturation attacks or tactical strikes beyond the front line. It is still unclear whether the missile can be reprogrammed mid-flight—a valuable feature for targeting moving or opportunity-based threats—but its mere existence already alarms Kyiv, especially after the damage inflicted by UMPK and UMPB glide bombs, the latter lacking their own propulsion.

The Banderol’s ability to be launched from drones or helicopters marks a significant shift in Russian operational doctrine. It allows the dispersion of attack vectors, reduces exposure of manned aircraft, and extends the range of force projection. This aligns Russia’s strategy with a growing trend also seen in the United States: integrating lightweight, modular, cost-effective cruise missiles into air-launched systems tailored to specific missions.

Ultimately, the emergence of the Banderol is significant not only for its military implications, but also for what it reveals about technological dependency, the fragility of international sanctions, and evolving battlefield tactics. According to the GUR, more than 4,000 foreign-made components have been identified across 150 Russian weapons systems examined—highlighting a structural failure in export controls. In other words, the war in Ukraine is reshaping the global defense industry and proving that modern conflicts are no longer fought solely with tanks and jets, but also with microchips, algorithms, and hidden civilian-grade parts embedded in the heart of modern weaponry.