Space holds stories that unfold at a different pace, as if time itself follows a different logic beyond our atmosphere. One such story resurfaced this week when the Soviet capsule Kosmos 482, launched in 1972 with the goal of reaching Venus, reentered Earth’s atmosphere and plunged into the Indian Ocean—reviving memories of the Cold War space race and sparking renewed debate about the growing threat of space debris.

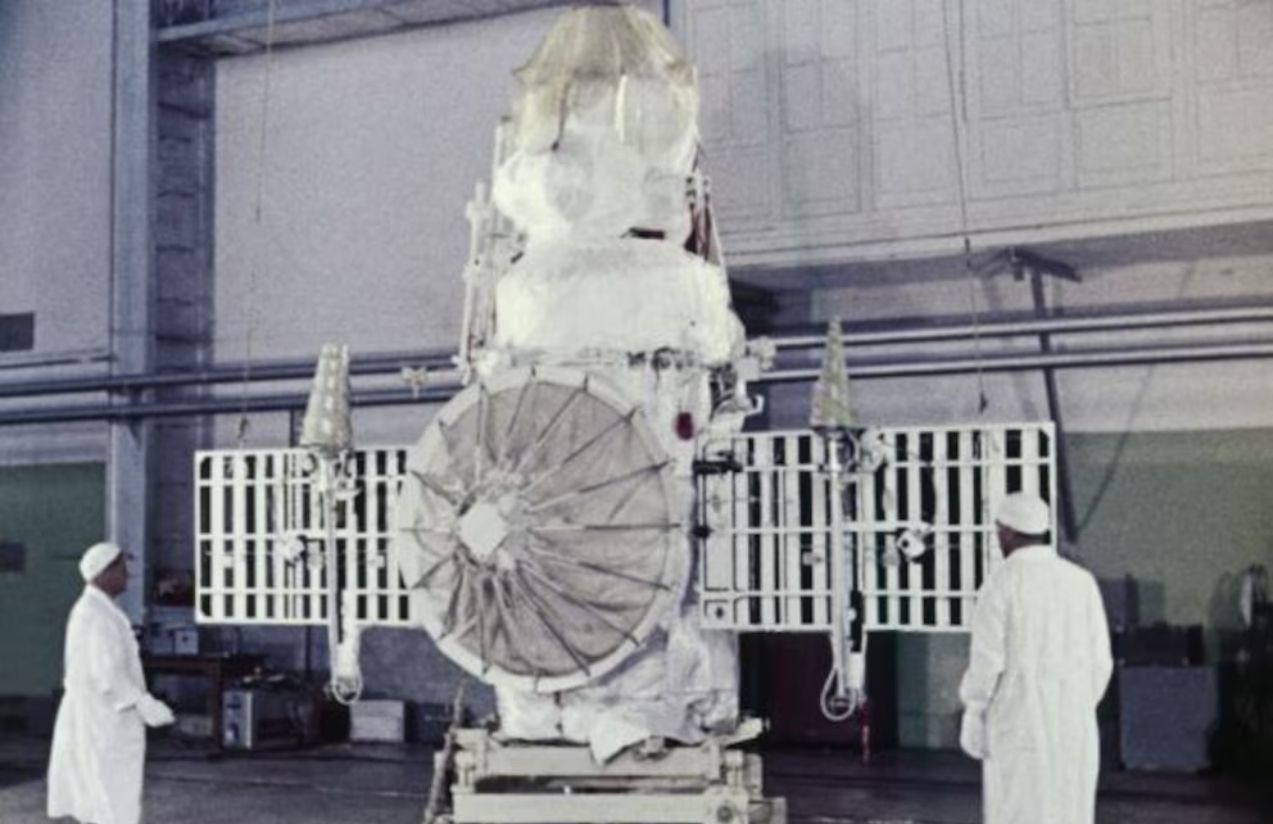

The probe was launched on March 31, 1972, as part of the Soviet Union’s Venera program, aimed at studying Venus’s atmosphere and surface. It was intended to be a twin mission to Venera 8, which successfully landed on the planet. Kosmos 482, however, never left Earth’s orbit. A malfunction in the fourth stage of the Molniya-M rocket prevented it from reaching escape velocity. The engine fired for only 125 seconds instead of the planned 192, cutting the mission short before it could leave the planet.

Though its primary objective was never met, the probe left a lasting mark. After a brief period of activity, the spacecraft broke into parts. Some fragments fell to Earth shortly after launch, but the most robust component—the descent capsule—remained in an elliptical orbit, between 220 and 9,800 kilometers above Earth. For more than fifty years, it circled the planet silently, unnoticed by the general public but closely monitored by space agencies and satellite trackers.

That long journey ended this past Saturday, when the capsule reentered the atmosphere and fell about 560 kilometers west of Middle Andaman Island, according to Russia’s Roscosmos space agency. The event had been closely watched by scientific organizations, which had spent days speculating about the exact impact point and whether any parts of the probe would survive the intense heat of reentry.

“The spacecraft ceased to exist after leaving its orbit and falling into the Indian Ocean,” Roscosmos stated in an official release, adding that the descent was tracked by an automated warning system for hazardous events in near-Earth space.

Astronomer Claudio Martínez told Argentine outlet Infobae: “The probe was still in orbit at 6:04 UTC. At 7:32, it was no longer there. In other words, it fell.” Though no eyewitnesses have emerged, Martínez noted that radar or civilian satellite footage could surface in the coming hours.

Kosmos 482 drew particular attention because of its design. Built to survive the dense and extreme atmosphere of Venus, the capsule’s durable titanium shell and 2.5-meter parachutes made it plausible that some components might survive reentry even after decades in orbit. Days before the fall, NASA had warned of this possibility.

Uncertainty surrounding the landing site caused concern in the scientific community. Predictions estimated the reentry would happen between May 7 and 13, with a wide margin of error. That meant any location between 52 degrees north and south latitude—including major cities like New York, Beijing, and London—was potentially at risk. Many of these were within the so-called “red zone,” a band of higher-risk areas spread across several continents.

Satellite tracker Ralf Vandebergh, observing from the Netherlands, followed the probe’s trajectory with precision. He captured high-resolution images showing an elongated structure on one side of the capsule, possibly indicating that the parachutes were still attached. But after half a century in space, no one could say whether the system was still functional.

Kosmos 482 carried scientific instruments that were never put to use: gamma-ray spectrometers to analyze Venus’s surface, particle flow detectors, a photometer for light measurements, and sensors for temperature and atmospheric pressure. All of it remained stranded in Earth’s orbit due to a single malfunction in the launch sequence.

Over time, the capsule’s orbit began to decay. Atmospheric drag—though slight—gradually pulled it closer to Earth. The original elliptical path, which once peaked near 10,000 kilometers, had shrunk to a quarter of that distance. Its fall was only a matter of time.

Beyond its technical implications, Kosmos 482’s return served as a stark reminder of a growing concern: space debris. According to the European Space Agency (ESA), over 1.2 million fragments larger than a centimeter orbit the Earth, including around 50,000 pieces over 10 centimeters. For more than fifty years, Kosmos 482 was part of that inventory.

Its story—a failed probe, long-forgotten but still orbiting, suddenly returning—raised pressing questions: How should legacy spacecraft be tracked? What risk do they pose? Who is responsible for the debris left behind in orbit?

While the capsule itself posed no direct threat, it forced a reassessment of orbital monitoring protocols. Its reentry may not have been glorious, but it was symbolic: a relic of Cold War ambition reminding the present of unresolved challenges in managing near-Earth space.

Fifty-two years after its launch, Kosmos 482 ceased to be a nameless object drifting through space. It fell, yes. But in doing so, it reignited conversations about the future of space exploration, orbital sustainability, and our technological memory. A fitting legacy for a spacecraft that never reached its destination.